Most sources of error due to confounding and bias are more common in retrospective studies than in prospective studies. Many valuable case–control studies, such as Lane and Claypon's 1926 investigation of risk factors for breast cancer, were retrospective investigations. Ī retrospective study, on the other hand, looks backwards and examines exposures to suspected risk or protection factors in relation to an outcome that is established at the start of the study. Prospective studies usually have fewer potential sources of bias and confounding than retrospective studies. All efforts should be made to avoid sources of bias such as the loss of individuals to follow up during the study. The outcome of interest should be common otherwise, the number of outcomes observed will be too small to be statistically meaningful (indistinguishable from those that may have arisen by chance). The study usually involves taking a cohort of subjects and watching them over a long period. retrospective cohort studies Ī prospective study watches for outcomes, such as the development of a disease, during the study period and relates this to other factors such as suspected risk or protection factor(s). Increasing the number of controls above the number of cases, up to a ratio of about 4 to 1, may be a cost-effective way to improve the study.

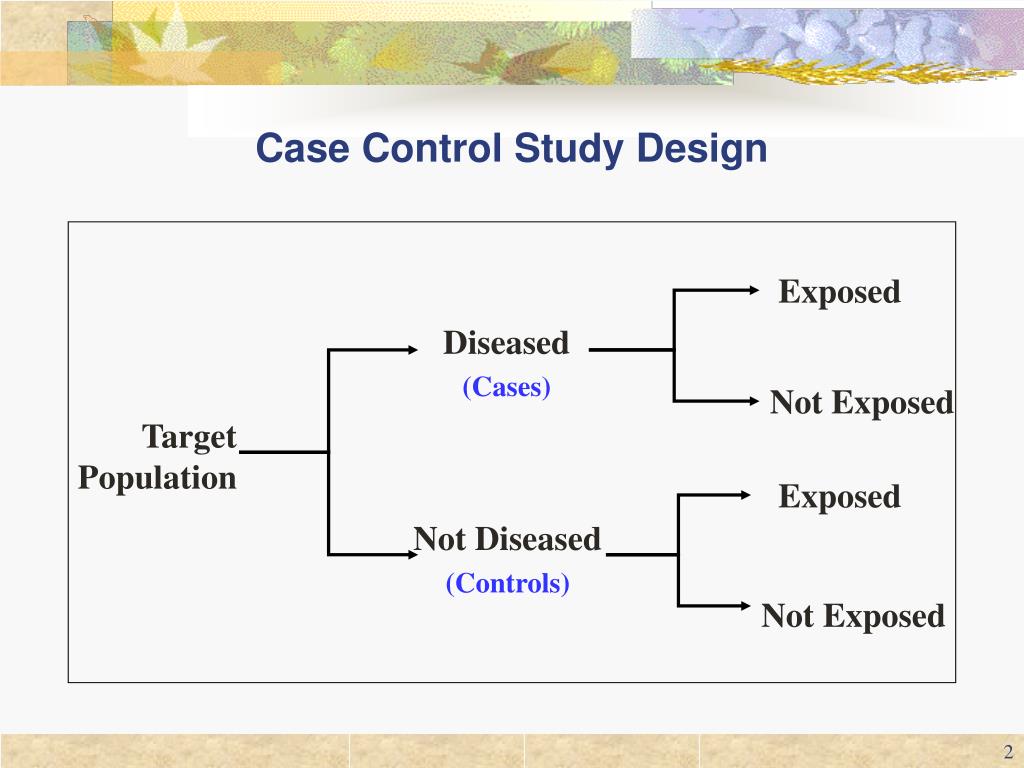

In many situations, it is much easier to recruit controls than to find cases. Numbers of cases and controls do not have to be equal. However, because the difference between the cases and the controls will be smaller, this results in a lower power to detect an exposure effect.Īs with any epidemiological study, greater numbers in the study will increase the power of the study. Ĭontrols can carry the same disease as the experimental group, but of another grade/severity, therefore being different from the outcome of interest. Controls should come from the same population as the cases, and their selection should be independent of the exposures of interest. Control group selection Ĭontrols need not be in good health inclusion of sick people is sometimes appropriate, as the control group should represent those at risk of becoming a case. The case–control study is frequently contrasted with cohort studies, wherein exposed and unexposed subjects are observed until they develop an outcome of interest. If a larger proportion of the cases smoke than the controls, that suggests, but does not conclusively show, that the hypothesis is valid. The potential relationship of a suspected risk factor or an attribute to the disease is examined by comparing the diseased and nondiseased subjects with regard to how frequently the factor or attribute is present (or, if quantitative, the levels of the attribute) in each of the groups (diseased and nondiseased)." įor example, in a study trying to show that people who smoke (the attribute) are more likely to be diagnosed with lung cancer (the outcome), the cases would be persons with lung cancer, the controls would be persons without lung cancer (not necessarily healthy), and some of each group would be smokers. Porta's Dictionary of Epidemiology defines the case–control study as: an observational epidemiological study of persons with the disease (or another outcome variable) of interest and a suitable control group of persons without the disease (comparison group, reference group).

An observational study is a study in which subjects are not randomized to the exposed or unexposed groups, rather the subjects are observed in order to determine both their exposure and their outcome status and the exposure status is thus not determined by the researcher. The case–control is a type of epidemiological observational study.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)